Stable Yard/Visitor Centre

The Visitor Centre and Tearooms are located in the restored barn and stable area which includes one of the original stables with elaborate stalls for five horses. A loft overhead would have been used for storage of hay and also tools.

The Visitor Centre and Tearooms are located in the restored barn and stable area which includes one of the original stables with elaborate stalls for five horses. A loft overhead would have been used for storage of hay and also tools.

Across the old cobbled stable yard lie the ruins of the coach and harness rooms. Various coaches were kept here and were washed from the water pump in the centre of the yard. Grain was stored in the coach house loft and above this was the dovecote. The keeping of doves and pigeons is believed to have been a medieval tradition, though it was also known in Roman times. Up until the late 18th century, when storable root crops became popular, it was difficult to feed stock over the winter and so many of the animals had to be slaughtered. This meant that fresh meat was often scarce. Many manor houses and monastic farms used pigeons to provide fresh meat and eggs and established dovecotes especially for this purpose.

Today the stonework in the old walls and buildings provides nesting places for birds such as wrens and starlings and also summer roosts for bats.

Lime Kiln

Lime kilns, which were once common in Ireland, are now scarce features in the Irish landscape. The lime produced in these kilns had many uses including as a fertiliser or to make whitewash and mortar. The kiln at Coole can be seen while walking the Seven Woods trail. The old quarry, now overgrown can be found nearby. The rock extracted was broken into small pieces and moved by horse and cart to the ramp at the back of the lime kiln.

Lime kilns, which were once common in Ireland, are now scarce features in the Irish landscape. The lime produced in these kilns had many uses including as a fertiliser or to make whitewash and mortar. The kiln at Coole can be seen while walking the Seven Woods trail. The old quarry, now overgrown can be found nearby. The rock extracted was broken into small pieces and moved by horse and cart to the ramp at the back of the lime kiln.

To make the fertiliser, the rock was loaded into the pit from the ramp at the back, with alternate layers of firewood, turf and rock. A fire was then lit at the bottom of the outlet. After a few days, the whole smouldering mass was sealed with a capping of watered lime. After a week, this resulted in the production of dehydrated (quick) lime. Water was added and the final product – hydrated (slaked) lime – was spread as fertiliser. The use of such fertiliser declined in the 19th century, when imported fertilisers came into use. Whitewash was used to cover and protect walls of houses and sheds in rural Ireland until recently.

The grid and barrier at the top of the kiln have been provided for safety and were not part of the original structure

Field Walls – Dry-stone Walls

A notable feature of rural Galway and Clare is the extent of stone walling built over many centuries to enclose fields and to determine boundaries. The use of stone for marking boundaries dates back 5,000 years.

A notable feature of rural Galway and Clare is the extent of stone walling built over many centuries to enclose fields and to determine boundaries. The use of stone for marking boundaries dates back 5,000 years.

The limestone walls at Coole date to at least 1776, when Arthur Young, in his “Tour of Ireland”, records a visit here. “He (Robert Gregory) has built a large house with numerous offices, and taken five or 600 acres of land into his own hands, which I found him improving with great spirit. Walling was his first object, of which I found him executing many miles in the most perfect manner.”

The double wall found in a section of the woodland called Pairc-na-Carraig – “rocky field”, lined a route for bringing stock from the farmyard and the lower farm fields to the turlough for grazing. The stock gap in the wall has been filled in but its outline can still be seen.

The higher sections of mortared wall found near the buildings and in the walled garden defined areas and provided shelter. Seeds that have lain dormant for many years in crevices can emerge and bloom in the right conditions.

Horse pump

In the 1850s Sir William had a pump installed to draw water from the lake up to the house, the remains of which can be seen today.

In the 1850s Sir William had a pump installed to draw water from the lake up to the house, the remains of which can be seen today.

A farm horse, coupled to a timber shaft, plodded a circular path to operate the suction pump which drew water from the lake and then underground pipes carried the water up hill to the main house.

Ha-ha

A ha-ha is the rather strange name given to a man-made ditch to either confine or exclude grazing stock. The concept is French in origin from the late 17th century and the etymology is often cited as meaning an expression of surprise at coming across such an amazing feature “ha ha” or sometimes “ah ah”. Whatever the origin of the word, one can be seen at Coole along the western boundary of the back lawn. This large open field of 6.5 hectares (16 acres) could then be grazed by sheep in the days before mechanical lawn mowers, while still allowing an uninterrupted view to the woodland, turlough and Burren hills beyond.

In the early days of Gregory family ownership of the Coole Estate, part of this field was used as a tree nursery. In 1776, when Arthur Young wrote his “Tour of Ireland”, he remarked on a visit to Coole: “Mr Gregory has a very noble nursery from which he is making plantations which will soon be a great ornament to the country.” When the Coole Estate was taken over by the Forestry Service, the back lawn was planted with conifer trees, which were removed in 2014 to allow for the natural regeneration of native species.

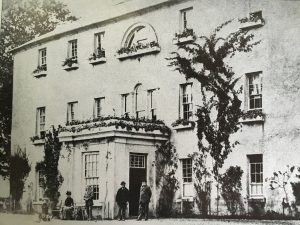

The House

The house, which was built c. 1770 by Robert Gregory, was a three storey building with six half levels, a square entrance porch and bay windows at the rear. The principal rooms of the house were the dining room (left rear as you face the site), and the drawing-room (right rear) with their bay windows facing the view of Coole Lough and the Burren Hills to the west. In between lay the library.

The house, which was built c. 1770 by Robert Gregory, was a three storey building with six half levels, a square entrance porch and bay windows at the rear. The principal rooms of the house were the dining room (left rear as you face the site), and the drawing-room (right rear) with their bay windows facing the view of Coole Lough and the Burren Hills to the west. In between lay the library.

Here Lady Gregory wrote her plays and books and was hostess to William Butler Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Douglas Hyde, Sean O’Casey, Edward Martyn, John Millington Synge and many others associated with the Irish Literary Revival movement.

This was also in early 20th century a happy house full of children’s laughter as it was home to Lady Gregory’s grandchildren, Richard, Anne and Catherine.

While the house no longer remains low walls have been rebuilt to show the original outline.

The Limestone Seat

Constructed in 1908, the limestone seat and was much frequented by Lady Gregory and her literary friends. It was placed under a large spreading Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata). Frequent visitors to this spot with Lady Gregory were her neighbours and co-founders of the Abbey Theatre, Edward Martyn of Tullira and William Butler Yeats.

The stone seat faces east, towards the Slieve Aughty mountains and the Persse estate of Roxborough. Roxborough House was home to Isabelle, Augusta Persse, until on her marriage to her neighbour Sir William Gregory she became Augusta, Lady Gregory.